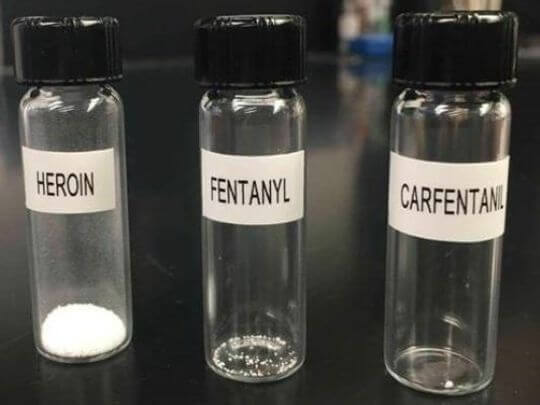

A visual of the dose of heroin, fentanyl and carfentanil needed to kill an average adult. (Photo: AP)

Much attention has been on the opioid crisis in recent years, but according to local law enforcement, meth continues to claim the crown in Greene County.

Meth on the streets today is cheaper, purer and more plentiful than ever, said Lt. Eric Reece, with the Springfield Police Department. “Meth is still our No. 1 drug of choice in this area,” Reece said.

Gone are the days of local mom-and-pop labs that make meth using the pseudoephedrine found in cold medicine. In 2005 — when methamphetamine manufacturing was at its peak in the Midwest —federal and state laws restricted the sale of over-the-counter cold medicines containing pseudoephedrine.

“The meth labs went away, which is a good thing,” Reece said. “We don’t have the environmental impact.” “The unfortunate part is now it all comes in from south of the border,” he said. “I’m not trying to get political with that, it’s just true. It’s all coming from down south.” In Mexico and other countries, meth-makers work in “super labs,” Reece said. “It’s not made in someone’s basement. It’s being made in a facility.” “It’s usually coming in at about 97 percent pure,” he continued. “It’s cheaper now. … We are paying less for better meth.” Reece said there’s been a “steady increase in seizures going back five or six years.”

Consequently, the Greene County Medical Examiner’s Office is seeing a sharp rise in fatal methamphetamine overdoses. Back in 2004, a time when locals made meth using cold medicine, there were seven fatal meth overdoses in Greene County, according to Chief Forensic investigator Tom Van De Berg. A decade ago, in 2008, Greene County had three fatal meth overdoses.

Compare those numbers with recent years:

- In 2015, there were 27 fatal meth ODs in Greene County;

- In 2016, there were 35;

- In 2017, there were 44;

- In 2018, there were 41.

“We are just seeing a lot of methamphetamine high-level overdoses,” Van De Berg said. “This new stuff they are bringing in is more potent.” Van De Berg said he, too, has noticed the decline in meth labs. “We used to go into houses all the time and see meth labs,” he said. “I haven’t seen one in a while.”

According to the Missouri State Highway Patrol, there were 189 meth labs discovered in Greene County in 2004. In 2018, there were three. Reece described those three meth labs as “lab trash.” “Somebody had taken the remnants and thrown it on the side of the road, which we have to go clean it up,” he said. “It’s not like we are going into a house where there’s a big lab operation set up. It’s where people are doing kind of like, one pot, where you basically make a user amount of meth with just a two-liter bottle and some tubing.” Reece said he and other investigators theorize that these “lab trash” incidents are likely old meth cooks who have recently been released from prison. “They are going back to what they know, which is cooking,” Reece said. “They probably don’t have the connections yet to get the better meth. … We don’t know that is true. We are just kind of speculating.”

David Stoecker is the advocacy and education outreach coordinator for the Missouri Recovery Network and co-founder of the Springfield Recovery Community Center. Stoecker is also in long-term recovery and a former drug dealer. He has been clean for more than 10 years. “They keep talking about meth making a comeback,” Stoecker said. “And I’m like, ‘meth never left.'”

In his view, the pseudoephedrine regulations might have made a positive impact briefly, but in the end, made the meth problem much worse. “It hurt us,” he said, shaking his head. “It opened it up for (drug cartels) to bring methamphetamine. “Now it’s cheaper and more pure than it’s ever been. Prohibition never works.”

What a meth overdose looks like

Methamphetamine is a stimulant drug usually encountered as a white, bitter-tasting powder. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, meth increases the amount of dopamine in the brain, which is involved in movement, motivation and reinforcement of rewarding behaviors. Short-term health effects include increased wakefulness, decreased appetite, and increased blood pressure and body temperature.

Long-term health effects include risk of contracting HIV and hepatitis; severe dental problems (“meth mouth”); intense itching, leading to skin sores from scratching; violent behavior; and paranoia.

Mercy ER Dr. Joe Jones spent 2012-2016 training in Cleveland, Ohio. During that time, he said never saw a single meth overdose. “Moving to Missouri and Springfield, it was somewhat of a surprise,” Jones said. “I see overdoses every day almost without fail.” Asked what a methamphetamine overdose looks like, Jones said it depends on how much the person has taken and their tolerance. The person is typically agitated, their heart is racing and they might be having hallucinations, he said. When a person dies from a methamphetamine overdose, that means they’ve had a cardiovascular collapse. “They get so agitated and their heart is racing. They get dehydrated. It’s as if they are giving themselves a heart attack,” Jones explained. “Their heart demands more blood flow than their body can deliver, and then you have a heart attack.” Jones said that if someone has been using meth and their blood pressure is high, their heart is racing, they are hallucinating and/or seizing, to please call 911 or bring them to the emergency department. “Be a calming force, because if they get agitated and heart racing, that is when they get at risk for cardiovascular collapse,” he said.

Opioids continue to be a problem

As far as fatal heroin overdoses, Van De Berg said that number has decreased significantly in recent years. Fentanyl deaths, though, have spiked. In 2015, there were 35 fatal opioid overdoses in Greene County (17 heroin, eight prescription opioids and 10 fentanyl). In 2018, there were 32 fatal opioid overdoses (seven heroin, three prescription opioids, and 22 fentanyl). And while the number of fatal opioid overdoses has declined slightly, that’s not to say opioids are on the decline in Greene County. Rather, more people today have access to and know how to use Narcan, the opioid overdose antidote. That means more overdose victims are surviving. It’s difficult to get an exact number of how many doses of Narcan were administered in a time period. Narcan is available without a prescription, and many first responders now carry it.

But looking at the number of Narcan doses administered by Cox and Mercy EMS throughout the region shows opioid overdoses continue to be a problem:

- 2015: Cox EMS administered 353 doses, Mercy EMS administered 360 doses

- 2016: Cox EMS administered 414 doses, Mercy EMS administered 384 doses

- 2017: Cox EMS administered 565 doses, Mercy EMS administered 524 doses

- 2018: Cox EMS administered 494 doses, Mercy EMS administered 455 doses

CoxHealth paramedic Kyle Meadows said he’s noticed the decline in opioid overdoses since 2017, a year he described as “our worst year, especially July and August.” “I remember it wasn’t unusual to have at least one of those type calls per shift,” he said. “There has been a noticeable decline.” Meadows said he believes the recent decline might be due, in part, to the community becoming more comfortable administering Narcan without calling 911. Meadows also points to better education about the dangers of opioid addiction and the CDC’s 2016 recommendations to avoid prescribing opiates to patients with chronic pain. “The really sad part is (opioids) affects everyone,” he said. “From kids to older adults. There are really no demographic lines that it stays within. It literally affects everyone equally.”

Fentanyl takes the place of heroin

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid that is often mixed with or sold as heroin to increase potency and profit. Though it is cheaper and easier to make (it is man-made, so there is no need for a crop of poppy plants), fentanyl is 50 times more potent than heroin. Again, going back to the number of fatal drug overdoses in Greene County, fentanyl-related deaths have surpassed heroin and prescription opioids in recent years.

•In 2015, there were 17 fatal heroin ODs and 10 fentanyl;

•In 2016, there were 16 fatal heroin ODs and six fentanyl;

•In 2017, there were 15 fatal heroin ODs and 29 fentanyl;

•In 2018, there were seven fatal heroin ODs and 22 fentanyl.

According to law enforcement, dealers often mix fentanyl with heroin without telling buyers. “If you are a heroin dealer, it’s cheaper to get fentanyl,” Lt. Reece said. “It’s more potent. A dealer can mix it with their heroin and double their weight.” “It’s easier to get, too,” he said, adding that fentanyl can be ordered online through the “dark web.” Reece said local law enforcement is seizing more and more product that is 100 percent fentanyl. “The user is not ready for that dosage, and we get the overdose deaths or just overdoses in general,” he said. A particularly scary thing Van De Berg said he is seeing is toxicology reports coming back showing the person had a deadly mix of methamphetamine and fentanyl.

Stoecker, who used drugs for years and now helps addicts find recovery, was puzzled by this. Based on his experience, Stoecker said it’s unlikely someone would want to mix a stimulant (meth) with a strong opioid such as fentanyl. He thinks the mixture is more likely accidental. “Imagine I’m a drug dealer and I’m selling cocaine, meth, heroin and fentanyl,” Stoecker said. “I’m going to use the exact same scales, the same scoops. So I think maybe it’s incidental. I don’t think people are doing it maliciously — adding it to cocaine and meth.” “That is really scary. With cocaine and meth, you have someone that is what they call opioid naive, which means they have zero tolerance to it,” he said. And not only do the unsuspecting buyers have no idea the product has some fentanyl in it, the people around them probably don’t know what to do in case of an opioid overdose, Stoecker said. “Like a group of kids at college that are having a frat party and somebody pulls out some cocaine and everybody sits there and does some lines of cocaine,” Stoecker said. “They are not going to have Narcan there. They are not going to know anything about it. I think it makes it a lot scarier.”